In my entire career of 43 years I have never seen more atrocity than I have seen in the incarcerated situations of Manus Island and Nauru.”

Paul Stevenson has had a life in trauma. The psychologist and traumatologist has spent 40 years helping people make sense of their lives in the aftermath of disaster, of terrorist attacks, bombings and mass murders, of landslides, fires and tsunamis.

He’s written a book about his experiences, Postcards from Ground Zero, and for his efforts in assisting the victims of the Bali bombings, the Australian government pinned an Order of Australia Medal to his chest.

Now, he says, it is the Australian government deliberately inflicting upon people the worst trauma he has ever seen.

Over 2014 and 2015, Stevenson made 14 “deployments” – as they are called in the militarised argot of those secretive worlds offshore – to Manus Island and Nauru, where about 1,500 asylum seekers who tried to arrive in Australia by boat are held on behalf of the Australian government. His role was to counsel and care for the mental health of the Wilson Security guards.

Stevenson is president of the Queensland branch of the Australian Democrats. The party is not registered in the state, so he is standing in this federal election as an independent, with the support of his party. He doesn’t know whether his slim electoral chances for a Senate seat – “somewhere between zero and a half” – will be helped or harmed by speaking to the Guardian. But he says he feels it is incumbent on those who have been inside Australia’s offshore detention centres to tell those at home the truth about regional processing.

He says he approached the Guardian, compelled by conscience to speak, “because I believe in our democracy”.

Over a career spanning decades Stevenson has worked with the survivors of the Port Arthur massacre, the Thredbo landslide, the Boxing Day Indian Ocean tsunami, the Bali bombings of 2002 and 2005. He has counselled diplomats after embassies were bombed, and families who have lost loved ones to bushfires and floods. Stevenson says that the great privilege – “the joy, even” – of working in the field of trauma is witnessing people fight back from cruel circumstance, working with people “who are incredibly brave, incredibly resilient, incredibly positively focused about what they’re doing”.

But there’s none of that in offshore detention. You don’t see the positive glimpses, you don’t see the strength of resilience, you don’t see the quirky little things that people do when the chips are down, you don’t see the laughter and you don’t see the bravery, and you don’t see any of those things that give hope for improvement in the lives of these people.

Every day is demoralising. Every single day and every night. And you can work an eight-hour shift, or a 16-hour-shift, or a 20-hour-shift, you can get up in the middle of the night to answer the calls to go down to the camp, and you know it’s not getting any better. And it’s that demoralisation that is the paramount feature of offshore detention. It’s indeterminate, it’s under terrible, terrible conditions, and there is nothing you can say about it that says there’s some positive humanity in this. And that’s why it’s such an atrocity.

The litany

The official Wilson Security “incident reports” from Stevenson’s time offshore, seen by the Guardian, are testaments to suffering.

More than 2,000 pages, they are awful and they are endless. The reports are brief descriptions of anything that happens in detention on the islands: any disturbance, no matter how small, is “written up”, classified and categorised, fed into the massive bureaucracy that maintains the island regimes.

But the language of the reports is cold and impersonal, a numbing litany of repeated acts of self-harm, of pointless fights and meaningless feuds, of abuse and misery and privation. The black letters carry a texture of depression.

The scale of distress blurs one report into another but, even amid the grim repetition, some stand out.

During Stevenson’s time on Australia’s offshore islands:

- Six boys, held on Nauru without parents, tried to kill themselves en masse, using the same razor blade.

- One woman attempted to kill herself seven times in five weeks, threatened to kill her own daughter, and had to be sedated to stop her repeatedly bashing her head into the ground.

- A woman, held on Nauru with her son, but facing permanent separation from her husband in Australia, carved his name into her chest with a razor because it “releases the feelings in my heart and I feel better”.

- An asylum seeker carved open his own stomach in protest at not being allowed to see or speak with his cousin, who was standing on a roof, threatening to jump.

- A three-year-old boy was allegedly molested by a guard but his mother was too scared of reprisals to report it until months later, when she was medevacked to Australia for a medical emergency.

- A refugee found naked and distressed – and who told authorities she had been sexually assaulted – was taken to the police station instead of the hospital. It was more than five hours after she went missing that she finally saw a doctor.

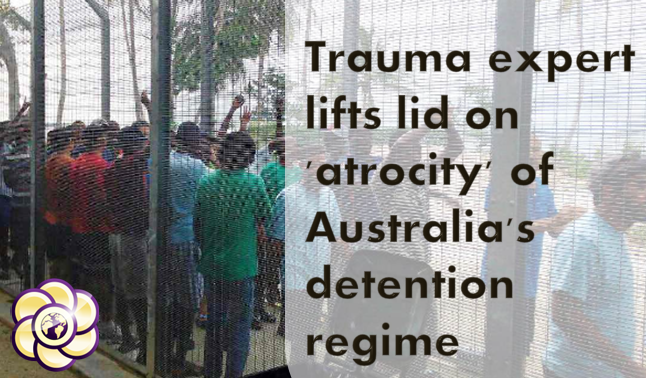

Protesters at the Manus Island immigration processing centre in May. The protesters were calling for an end to their detention, which the Papua New Guinea supreme court ruled illegal

Stevenson’s job on Manus Island and Nauru was to counsel the Wilson Security guards so that they were able to do their jobs – keeping safe and under control those held in the offshore detention centres. But Stevenson says he “made it a part of my job” to understand the lives of those held, as well as those holding.

“I have to be very certain as to what’s happening in the lives of the asylum seekers in order to help the guards to be able to manage those situations.

“After every critical incident, I would go down into the camps, and I would talk to the people who were involved in those incidents, and in doing so, I would come into contact with the real issues that were occurring in the camp.”

Most of the guards are from military backgrounds, many have served in the Australian and New Zealand armies on overseas deployments. Some of those, Stevenson says, were well-suited to the job, passionate about caring for the asylum seekers’ welfare, and proud to be doing the best they could in difficult circumstances and an oppressive physical environment.

“But the bulk of people were there for a different reason, and that is to get a good income in a very short period of time for their own personal reasons … they were there to work.”

The trauma of offshore detention does not discriminate, Stevenson says. All who exist in that environment, as jailed or jailer, are scarred.

“More than anything, there’s a demoralisation about the work the guards do. The people who are very compassionate and concerned about their work burn out pretty quickly … those who are probably the better people probably burn out earlier, and those who are more disconnected to their job, those who dissociate more from their clientele, probably tend to last longer.”

“I’ve seen it, in terms of a good person burning out, I’ve seen it in one deployment. One week, two weeks, people who have done one deployment … and never come back for a second.”

That demoralisation – and the struggle the guards face reconciling their task with their empathy – is starkly apparent in the incident reports.

“Hanging and choking and head butting and swallowing pills and nails and detergent … goes on as a matter of course”

Paul Stevenson

In one report, an asylum seeker is initially referred to by his six-character boat ID – when Stevenson first arrived on the islands no one in detention was referred to by their name – but as the report progresses, through the bureaucratese emerges a moment of genuine communion and humanity.

I was talking to client [ID NUMBER REDACTED] as I notice he was relocating his bed from the rec area to the trees near C10, he was saying his UN meeting this morning was no good. Trying to lighten the mood, I said it will be good when the new buildings go in. [FIRST NAME REDACTED] replied ‘I no have friends, I won’t be needing a room, a bed, any food or water. It’s just me now’. He then said he is tired and closed his eyes and tears rolled down his cheek. He told me he had just spent 70 minutes on the phone to his wife. His wife is being pressured to divorce him and leave him here.

Code blue

Nauru and Manus are lands with their own language.

Reports are littered with acronyms and initialisms, conversations contaminated with code and call signs.

A “code green” is a security breach or an escape. A “code black” is a request for assistance, usually to break up a fight.

A “code pink” on Nauru is when the women of the camp go naked in protest, sending camp managers scrambling to find female guards to watch them, who then often have to work double shifts.

But by far the most common call signal on the radio is “code blue”. Code blue is a medical emergency, almost invariably a suicide attempt or act of self-harm. The call goes out over the radio and everybody responds, Stevenson says.

“You see people drop everything and run to the site, but I think that’s got something to do with whatever is happening in their day too. These are the moments that some people live for, because all of a sudden there’s a bit of excitement.

“In a 12-hours shift, you can have 11 hours of sheer monotony, and then all of a sudden the alarm bells are going, people are racing to the scene. There is an excitement about it.”

But the constant criticality of the environments of Nauru and Manus both desensitises and wears on those who have to live and work there.

Some days there are four, five, six code blues: a razor blade swallowed; washing powder ingested; somebody found hanging and cut down by a guard using hook knives issued for that very purpose; mothers trying to kill themselves in front of their children. One desperate attempt after another.

“It does become very normal and people become very desensitised to it … so we find that even amongst the guards, there’s a desensitisation to a whole range of traumas.

“If there’s six or so [suicide attempts] in a day, then you’re starting to get an attrition about that.”

But beyond the moments of grim intensity lies the numbing monotony of long, slow hours and days.

“Every critical incident will be followed up by maybe 12 hours on close observation, and so the next staff member spends 12 hours standing in the opening of a tent watching somebody, and that’s their entire shift.”

Shifts spent on “high watch”, also known as “arm’s length watch”, involve a guard monitoring a single asylum seeker from a distance no greater than arm’s length, in order to stop them hurting themselves. It means watching them sleep, walking behind them everywhere they go, writing down everything they do or say.

It is humiliating for an asylum seeker – an advertisement to the entire camp of a mental breakdown or unsuccessful suicide attempt – and grindingly boring for the guard.

In offshore detention, self-harm has become a “currency”, Stevenson says, a tool used as leverage to win some perceived advantage, no matter how small, debasing, or ultimately self-defeating it might be.

People might be attempting suicide because they cannot stand their lives in detention and they want to die, or they might be self-harming because they want to be transferred to an air-conditioned seclusion tent, or because they want to attract attention within the camp or back in Australia.

“Torture and incarceration is considered to be the most demoralising situation that people could be in”

Paul Stevenson

“This is what detention does to people,” Stevenson says. “It turns them against themselves to use themselves as currency. And that’s a very very significant level of traumatisation, when somebody does that. All they have is their own body to negotiate with. If we’re in any way supporting the development of that very, very mentally unstable phenomena we need to do something about that.”

Two refugees have deliberately set themselves on fire this year on Nauru. Iranian Omid Masoumali died in a Brisbane hospital two days after his immolation. A female Somalian refugee transferred more quickly to Australia survived her self-immolation and remains in hospital in Australia. Another woman locked herself in her room and set it on fire, in what was reportedly a suicide attempt. She too, survived. But the brutality of these acts have shocked Australia.

Stevenson says they were entirely predictable.

“The self-immolations are definitely an expected outcome. Whether or not it was a serious suicide attempt, it’s hard to say, because in the self-harm activities, which is a currency on the island, you never know how far it’s going to go. You never what a burning was intended to be, and you never know whether or not it got out of control and got so much worse than it was intended to be. Certainly hanging and choking and head butting and swallowing pills and nails and detergent and all that … goes on as a matter of course.”

Children regularly witness their parents committing self-harm, or are forced to intervene or raise the alarm.

The incident reports reveal that in January last year one girl watched as her mother swallowed screws in an attempt to harm herself. When guards came rushing to intervene trying to prise the screws from her hands, the girl told them she had already swallowed two, as her mother fought the guards telling them: “It’s too late, it’s over.”

When children are not witnessing acts of self-harm, they are committing them themselves.

Just after breakfast on 26 September 2014, six young boys – all on Nauru without parents or family – all attempted to kill themselves at once. They were found bleeding and initially refused any medical assistance.

After the emergency response team – the armed squad used to respond to riots – was called in, a single, bloody blade was taken from the boys and they were treated for their wounds before being moved to another part of the detention centre for observation.

Limbo

Post-traumatic stress disorder is all pervasive in offshore detention. Asylum seekers held on Nauru and Manus are more likely to suffer PTSD than victims of terrorist attacks, shootings, floods and bushfires, Stevenson says.

It cannot be effectively treated because it is the fact, and the nature, of detention itself that causes it, Stevenson says.

In the aftermath of a natural disaster, a catastrophic flood or bushfire, incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder is about 3%.

After a terrorist attack, the incidence is about 25%, “and that’s because it’s considered to be an unnecessary trauma that somebody has perpetrated against them”.

“But when you get up to torture and incarceration, that figure jumps up to 50% because torture and incarceration is considered to be the most demoralising situation that people could be in in their lives: with no control, they are absolutely desperate, with no way of knowing what’s going to happen, and probably knowing that nothing’s going to happen at any time, and so this is going to keep on going for ever and ever and ever.”

Because, beyond the conditions of detention, it is the absence of a future, even the hope for one, that demoralises those in detention.

The refugees “resettled” in Papua New Guinea have almost all returned to Manus – even trying to break back into detention in some circumstances – because they do not feel safe outside. They have been beaten, robbed and left homeless in PNG. Their permits to live in the country have expired already. It is a bitter irony that they are now “illegal” for the first time in their long, sorry sagas.

Nauru will not permanently resettle any refugees. Already, the tightly woven monocultural fabric of the small island community has been rent by the arrival of the asylum seekers and refugees, who now make up more than 10% of the entire island’s population. Tensions regularly run high between locals and refugees, and violence is common. Hostility, though not absolute, is prevalent.

The refugees know they cannot stay longer than the five years Nauru has granted them. The temporary “travel documents” they have been issued are worthless. They do not allow anyone to travel anywhere. No one has been allowed to leave the island save for in the most desperate medical circumstances.

“Resettling refugees in Papua New Guinea: a tragic theatre of the absurd”

David Fedele

Read more

The $55m “Cambodia solution” has been an unalloyed failure. Every single refugee sent to that place has since left, taking their chances in the homelands from where they initially fled a “well-founded fear of persecution”, recognised by both Australian and Nauruan authorities.

So the refugees remain in a bleak, Kafkaesque limbo, with no direction in which they can turn, no way out apparent. Many have been in detention more than 1,000 days. For most, going home is not an option.

“The reason these people don’t just go home is because home is a known quantity for them,” Stevenson says. “It’s not changed. They are in very real threat of torture and trauma and perhaps death returning home.

“They know that their children have no future if they return home. While they are treading water in this place, where they are fed three times a day, and if they do have a need for medical attention they’ll get it, this is as good as it gets for them. But they know what it’s like to return home, they fled their home for that reason.”

Many, too, Stevenson says, still believe they will ultimately, make it to Australia, “if they can just see it out”.

But slowly, inexorably, those held on Nauru and Manus are worn down by their incarceration, or by the uncertainty of life outside the camps but still on the tiny islands they regard as prisons.

On Nauru, family structures are fraying and fracturing. Children, recognising their parents have no authority over their own lives, refuse to obey them, defying them because they know the guards hold all the power.

Children ask for keys as a birthday present, because, knowing only a life of detention, they know the power that keys hold: the chance at liberty.

‘The better parts of Nauru’: asylum seeker children share footage from inside detention

And parents, helpless to offer their children any sense of a future, because they have none of their own, give up. Stevenson says:

The impact that it has over time on the asylum seeker is … a kind of demoralisation syndrome. And so, what you find on a day-to-day level, is that people relinquish their responsibilities of all kinds. They’re living in a wire cage, and their every need is being serviced by someone else, and they have no control over that. They have no control over when they’re fed, how long they can spend in a shower or toilet, they have no control over their lives, so people relinquish control, and they vegetate, they start to get into this dissociative vegetative state that we know is very common with trauma, and then everything suffers.

Domestic violence increases for example, in the heat, and the oppression and the monotony and boredom that goes along with it, we get lots of lots family domestic stuff to deal with. At the other end of the scale, you get parents relinquishing their authority over their children, because their children are cared for. Children go away to school during the day then Save the Children [which has since left the island] come in and do some activities with them, and they’re kept busy and … we find that the parents relinquish their parenting skills and their parenting obligation to the children. The children, you don’t have to watch them, they can run around in the compound, they’re not going anywhere. Parents dissociate from their children, and pull back.

Closed world

There is no peace for an asylum seeker in offshore detention. Everywhere they go, they are watched, monitored, corralled, controlled. They have no agency over their own lives, hollow existences that have been stripped of dignity and purpose.

“Cruelty to asylum seekers dressed up as compassion is the scandal that bedevils Australia”

Antony Loewenstein

They are observed while they sleep, watched while they shower,

“The monitoring is extreme. We have guard posts and we have roving guards and there is no area that is out of scope of the guards. People live in tents, remember, and they walk around by the tent doors and they peer in. Everything is open view.”

In detention, their use of phones and internet is heavily monitored. People are spied on by a regime paranoid about information leaking out.

One incident report reads: “[CLIENT ID REDACTED] opened his Facebook page. On the page were pics of protests/political nature. He sent a message to a male and a female. He viewed a page with the initials RACS Refugee Sydney. He left and spoke to some friends, pointing to the internet rooms and spoke to another client (unknown) for about 20 mins.”

“It’s just their way of putting a big net around it and saying, ‘Nobody shall see what is actually going on here”

Paul Stevenson

Secrecy pervades, Stevenson argues, because “we want to lock these people away”.

“We want to put them out of sight and out of mind. We don’t want the Australian public to really know what goes on there. And because we can. We can lock down the airport, we can do it, it’s easy to do it. You can’t take a camera into a compound, you can’t even take a mobile phone in – not even staff can do that.”

“If you’re caught taking a photograph, even as a staff member, you can be prosecuted for that. It’s just their way of putting a big net around it and saying, ‘Nobody shall see what is actually going on here.’”

The world of offshore detention is not one to be shared with the outside. It exists in the shadowlands, in distant, remote places behind high wire fences. The regime is not to be questioned.

But, Stevenson says, for the health of Australian democracy, it must be. He says while he was on the islands he “didn’t hold back” in criticising the system he was working within.

“I had plenty to say about what was happening at the time, and I made sure that I got to the right people to inform them about the traumas that were occurring and I didn’t hold back on my opinions on what could be done better.

“But I have to concede that … nothing changed as a result of anything that I had to say.”

His membership of the Democrats, his previous candidacies for parliament, and his future ambitions, were known while he worked on Nauru and Manus. His employers were not troubled. “Not at all, in fact I received a lot of encouragement.”

Stevenson says he is speaking up now, because, in an election campaign in which the issue of asylum has been made fundamental by both major parties, he believes the Australian people do have a right to know what is being done in their name, and with their money.

“The consequences are such that my career could end tomorrow because of what I am saying today … but values stand for nothing unless they’re coupled with the courage of conviction.”

“I do have a political agenda, and I don’t hide it. I’m very much of the opinion politically, that Australia should do the honest, decent thing. We have the ability to give people a new start in life. And I think it’s shameful that our politicians are bipartisan in stopping this from happening.”

To access the full article and video, use source link below.

Note: The day after psychologist Paul Stevenson tells the Guardian conditions on Nauru and Manus Island are ‘demoralising’ and ‘desperate’, his contract is cancelled. The trauma specialist whom the Australian government awarded an Order of Australia for his work counselling victims of the Bali bombings, had undertaken 14 deployments to Nauru and to Manus Island in Papua New Guinea.

By Ben Doherty and David Marr

(Source: theguardian.com; June 20, 2016; http://tinyurl.com/hvmbguk)